Comparative Political Economy of Six Economic and Organizational Models

8/6/2025

Introduction

The structure of an economic system is not a neutral technical arrangement; it reflects deep political, social, and ideological commitments. To compare economic and organizational models is to explore how societies allocate power, distribute surplus, and define the relationship between capital, labor, and production. This analysis examines six models—Ethosism, Co-operatives, Capitalism, Socialism, Participatory Economics (Parecon), and Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs)—through the lens of ownership, governance, remuneration, surplus distribution, and systemic adaptability.

Some of these are full-fledged macroeconomic systems (Ethosism, Capitalism, Socialism, Parecon), while others operate as enterprise-level structures (Co-ops, ESOPs) embedded within broader regimes. Of these, Ethosism introduces the most structurally disruptive proposition: the elimination of salaries altogether in favor of a fully participatory and negotiated profit-sharing regime.

1. Ethosism: Dynamic Participation and the Elimination of Salaries

Ethosism challenges the foundations of both capitalism and socialism by banishing salaries and viewing labor and capital as continuously renegotiated contributors to value creation. Instead of fixed remuneration, 100% of profit is distributed among all participants based on agreed-upon shares that reflect expected value contribution, historical performance, and role criticality.

Crucially, these shares are not fixed. Every new hire or new investor triggers a reconfiguration of the entire profit-sharing structure. The process is inherently dynamic and deliberative, requiring transparent justification for each participant's share. There is no class-based split (e.g., 50% to labor, 50% to capital); rather, the system is rooted in fluid proportionality and democratic negotiation.

Ethosism thus reframes economic participation not as employment, but as a continuous contractual relationship of contribution. It encourages lean governance, values transparency, and treats technology as a tool for maximizing universal participation—not profit

2. Co-operatives: Democratic Ownership Inside Market Constraints

Co-operatives are worker- or member-owned enterprises where decisions are made democratically, typically using the principle of one member, one vote. Workers may receive wages, but also share in the surplus based on their labor or patronage.

While co-ops democratize ownership and blur the labor-capital divide, they generally operate within competitive market economies, where wages and managerial hierarchies can still resemble capitalist firms. Their democratic intent is clear, but their capacity to transform economic relations is often constrained by external market forces

3. Capitalism: Profit Maximization Through Wage Labor

Capitalism centers on private ownership of capital and the commodification of labor through the wage relation. Owners provide capital, hire labor, and extract surplus in the form of profit. Workers receive fixed compensation, typically unrelated to firm profitability.

Capitalism’s strength lies in its incentive structure for investment and innovation. However, the system structurally separates risk and reward—owners reap the profit, while workers bear the precarity. The wage relation also entrenches systemic inequality by institutionalizing labor as a cost to be minimized.

4. Socialism: Public Ownership and Centralized Allocation

Socialism aims to eliminate private ownership of production and instead vest it in the state or collectives. Wages are administered through centralized planning, and surpluses are redirected into public services or reinvested into the commons.

The system emphasizes equality, access, and redistribution, but can suffer from bureaucratic centralization and detachment from micro-level productivity signals. While socialism may guarantee employment and social welfare, it often lacks responsive mechanisms for recognizing individual contributions or local innovation.

5. Participatory Economics (Parecon): Planning by Councils and Effort-Based Rewards

Parecon seeks to eliminate market allocation and hierarchies by instituting participatory planning through worker and consumer councils. Individuals are remunerated not by productivity or profit, but by effort and sacrifice, as judged by peers within balanced job complexes.

The model embeds horizontalism and equitable distribution at its core. However, it demands high levels of administrative coordination and collective engagement to function at scale. While Parecon advances moral clarity on fairness, it raises operational questions about agility, complexity, and innovation.

6. ESOPs: Partial Democratization Within Capitalist Enterprise

Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs) give workers ownership shares—usually through retirement accounts or corporate programs—while maintaining traditional corporate structures. Workers receive fixed wages and may receive dividends as shareholders.

Though ESOPs promote wealth-sharing, they rarely alter governance hierarchies. Decision-making power remains largely with executives or legacy capital holders. ESOPs are thus reformist tools—improving income distribution without restructuring the core wage-profit dichotomy.

Comparative Reflections

When comparing alternative economic systems through the lens of political economy, key structural distinctions emerge in how each model approaches remuneration, ownership, risk, adaptability, and incentives. These dimensions are foundational to understanding how value is created, distributed, and governed.

Remuneration Logic: Among the surveyed models, only Éthosisme and Parecon fully decouple income from traditional fixed wages. Éthosisme operates on a system of negotiated profit shares, tying income to evolving participatory value. Parecon, by contrast, links compensation to peer-assessed effort, emphasizing fairness through collective evaluation. Other systems—capitalism, cooperatives, and ESOPs—retain a wage-dividend hybrid structure.

Ownership Structure: Ownership varies widely. Capitalism and ESOPs preserve private property rights, though ESOPs distribute ownership internally among employees. Socialism places ownership in the hands of the state or public institutions. Cooperatives and Parecon collectivize ownership, often through member-based or sectoral models. Éthosisme departs entirely from fixed ownership by introducing a fluid, non-static stake based on one’s evolving contribution and participation in value creation.

Risk Distribution: Risk asymmetry defines capitalism, where capital owners externalize much of the downside. Éthosisme aims for symmetric risk-sharing, aligning exposure with actual participation. Cooperatives and ESOPs mitigate risk by internalizing it among workers, albeit partially. Socialism treats risk as a collective responsibility. Parecon spreads risk through decentralized participatory planning units.

Structural Adaptability: Éthosisme stands out as dynamically adaptive, recalculating distribution and stakes in real time as inputs and conditions change. Capitalism, while operationally flexible, channels gains disproportionately. Socialism often exhibits rigidity due to central planning constraints. Parecon prioritizes equity and participatory balance, but at the potential cost of responsiveness to rapid economic shifts.

Incentive Alignment: Éthosisme directly ties reward to evolving contribution, integrating moral and economic incentives. Capitalism ties rewards to capital ownership, often irrespective of labor input. Socialism abstracts reward into egalitarian principles, potentially flattening motivation. Parecon links reward to perceived effort, aiming for fairness but relying on intensive peer surveillance. ESOPs hybridize fixed salaries with shared profits, creating a dual incentive structure that partly democratizes surplus distribution.

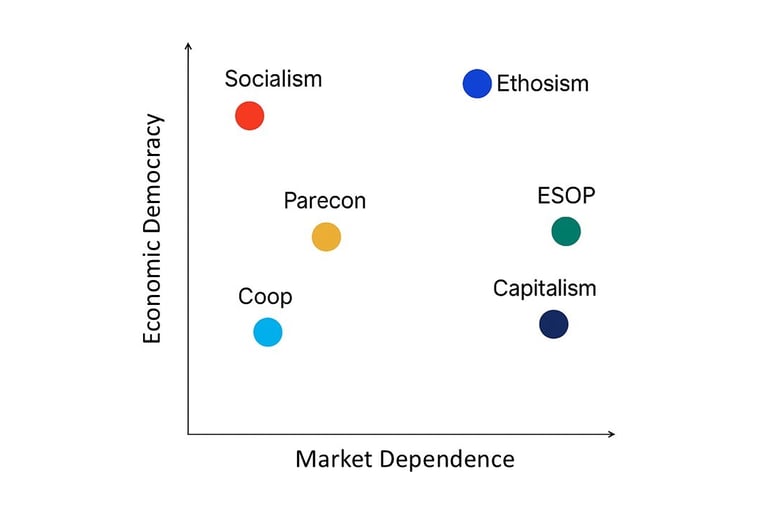

Spatial Comparison Framework:

The six models along the dual axes of economic democracy and market dependence reveal the underlying tensions between collective governance and market imperatives. Socialism prioritizes democratic control with minimal market influence, often resulting in centralized planning, limited consumer choice, and inefficiencies in resource allocation. Capitalism, in contrast, relies heavily on markets with little democratic input, concentrating economic power, widening the wealth gap, and subjecting essential needs to profit-driven logic, often at the expense of environmental sustainability. Ethosism disrupts this opposition by combining high economic democracy with full market engagement; it remains profit-driven, but for all, redistributing decision-making and returns across the economic body rather than concentrating them at the top. Models like Parecon, cooperatives, and ESOPs occupy the middle ground, blending shared governance with selective market use, but often face trade-offs in scalability, operational efficiency, and consistent equity.

Example Scenario: A Solar Panel Manufacturing Enterprise

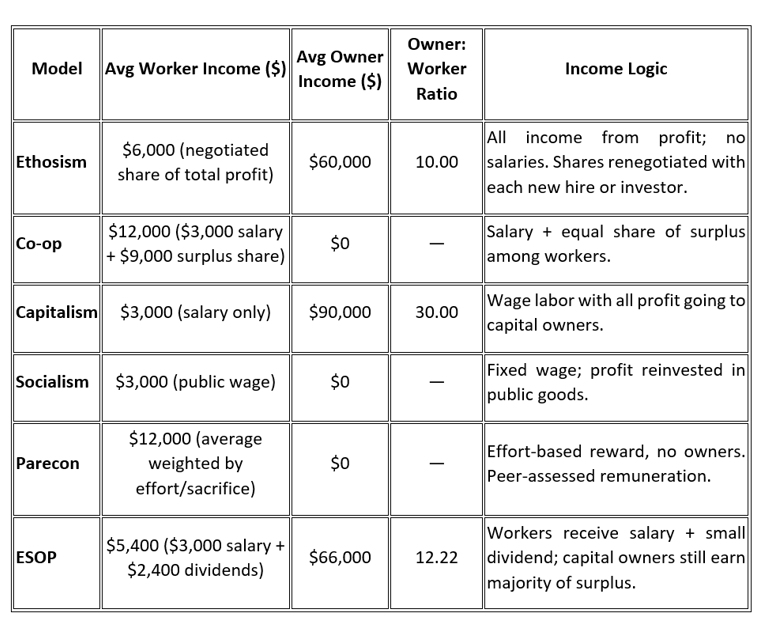

To illustrate the practical implications of each model, let us consider a hypothetical enterprise: a mid-sized solar panel manufacturing company. It generates $1,000,000 in monthly revenue and incurs $400,000 in operating costs (excluding worker compensation). The net profit available for distribution is thus $600,000. The workforce includes 50 employees, and the firm has 5 investors or capital contributors.

Assumptions:

Number of workers: 50

Number of owners (if any): 5

Net profit: $600,000/month

Fixed salary where applicable: $3,000/month per worker

Mathematical Comparison by Economic Model

Insights:

Ethosism offers a proportional system where all contributors (regardless of role) earn a negotiated percentage of the profit. The ratio can vary but is democratically adjusted and transparent.

Co-ops and Parecon maximize worker income by fully eliminating external ownership or salary-profit divides.

Capitalism generates the largest inequality, with workers receiving a fixed wage and owners capturing most of the surplus.

Socialism ensures predictability and equity in income, but disconnects it from enterprise performance.

ESOPs are hybrid systems where workers gain some profit-sharing benefits but remain structurally subordinate to capital owners.

Ethosism stands out in these models not because of a fixed formula, but because of its adaptability: each change in team structure (new hire, new investor) requires collective recalibration of profit shares. This builds a culture of participation, transparency, and responsibility, rather than compliance with static salary norms.

This solar panel case underscores the different logics of value attribution embedded in each system—and the deep political assumptions they carry about fairness, risk, and reward.

What about the Public Sector

In examining the role of the public sector within different economic systems, only full-fledged macroeconomic models—namely Capitalism, Socialism, Parecon, and Ethosism—provide sufficient structural scope to merit comparison. Organizational models like cooperatives or ESOPs function within existing systems but do not offer a comprehensive framework for public sector management and financing.

Under Capitalism, the public sector mirrors many of the structures found in the private sector. Public servants are paid fixed salaries, determined by formal job classifications, civil service contracts, or political bargaining. While the public sector is ostensibly shielded from the volatility of the market, in practice, its structure and budget are heavily influenced by prevailing market ideologies and the fiscal priorities of elected officials. Salaries may reflect market rates, but rarely do they reward innovation or mission alignment beyond basic performance metrics.

In Socialism, public sector employment is grounded in centralized planning. Compensation is standardized and decoupled from individual productivity or market dynamics. Public servants receive fixed salaries, set by the state, with the primary objective of maintaining equity and universal access to employment. While this fosters uniformity and collective responsibility, it often results in a rigid bureaucracy and limited incentive for innovation or responsiveness.

Parecon, or Participatory Economics, also retains the concept of fixed compensation for public servants but reconfigures how it is determined. Salaries are calculated based on effort, sacrifice, and socially recognized job complexity, all evaluated within nested participatory councils. The aim is to foster equity and democratic control without defaulting to centralized fiat or market logic. Public servants, in this model, remain salaried workers, though their earnings reflect deliberative, peer-based assessment rather than top-down decisions or impersonal market forces.

Ethosism departs radically from the notion of salaries. In this system, public servants are not compensated through fixed monthly wages. Instead, their remuneration comes from a percentage of the budget allocated to the department or structure in which they serve. This share is not uniform but varies according to the size, scope, and performance of the unit. Assignments are determined by a direct chain of command, but the actual income of the public servant is inseparable from the fiscal health and strategic use of the departmental budget. Rather than functioning as passive executors of state policy, public servants in Ethosism are co-stakeholders in their institution’s success. Their income fluctuates with the structure’s performance and resource stewardship, embedding fiscal responsibility and collective mission into the very design of public administration.

This comparison reveals how each system defines the social contract between the state and its servants—whether through market emulation, centralized planning, participatory deliberation, or dynamic budget-sharing. Ethosism, in particular, challenges the idea of public service as salaried labor, recasting it as an active and fluid engagement in the governance and management of shared resources.

Conclusions

These models are not merely economic schemas; they are political architectures. Each is grounded in an ideological vision of what constitutes justice, freedom, and responsibility. Éthosisme stands out by discarding both the wage system and class-based allocation in favor of a continuous negotiation of contribution and entitlement. Its radical premise challenges us to rethink the very meaning of “earning.” Each model carries its own trade-offs between efficiency, equity, and participation. Rather than treating existing systems as endpoints, they should be understood as evolving frameworks—unfinished experiments in how societies organize work, distribute power, and define value creation.

Ultimately, the task is not to rank these models, but to interrogate their ideological foundations, institutional mediations, and the value conflicts they encode. In a Polanyian sense, these systems are not merely economic mechanisms but socially embedded constructions shaped by political and moral choices. Rather than treating them as static blueprints, they should be understood as evolving frameworks—unfinished experiments in how societies organize labor, distribute power, and construct notions of value. Their relevance lies not solely in internal coherence, but in the political questions they compel us to confront: Who decides? Who benefits? And at what cost? In this light, they urge us to rethink the economy not as a separate domain, but as a contested space where struggles over justice, real freedom (in Sen’s sense), and the unequal distribution of life chances unfold.

Jo M. Sekimonyo

Email : sekimonyo@hotmail.com

Website : https://sekimonyo.com/

ORCID : 0000-0002-5358-2986